A few years ago The Economist said, ‘Since World War II every recession has been caused by financial crises and oil shocks’. At the risk of making The Economist obsolete, it pretty much nailed the major root causes of our economic problems in one sentence. I was born in 1973, I’ve lived through four oil shocks in my lifetime, and now one gas panic. All were caused by factors completely beyond the control of the UK.

The 1973 shock was caused by the Yom Kippur War and, after many years of talk, OPEC finally managed to engineer a spike in the oil price. The 1979 oil shock was caused by the islamic revolution in Iran, as despite initial assurances, Iran decided not to sell into global markets in the same way as before. The 1990 oil shock was caused by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, and well-founded fears about destruction of oil wells in both countries. The 2008 oil shock was caused by a rise in demand from China, a booming economy at the time, something established oil producers had not planned for. Now gas prices are through the roof due to two reasons the UK can’t control – the war in Ukraine and the mass shutdown of nuclear power plants in France, which has reversed normal flows of electricity via interconnectors. France has hitherto been an exporter of electricity, but cross-channel connectors are now sending the best part of 3000 megawatts to France from the UK.

The fact that oscillations in fossil fuel prices can cripple the global economy is well-known, but we are closer to weaning ourselves off of fossil fuel dependency than ever before. Completely ditching gas for electricity production in the UK could take another 12 to 15 years. It’s possible at the current rate of renewables installation, however. It won’t be a quick or easy process, but aside from the environmental benefits the economic prize is huge – electricity from affordable sources at stable, predictable prices. It will amount to the difference between living at the foot of an active volcano and sitting pretty in the middle of a tectonic plate.

What of the current gas panic? The UK needs short-term intervention this winter, and beyond that an overhaul of the electricity market and how it’s priced up. There is much debate about the merits of interventionist schemes, the first proposal, from my party the Lib Dems, proposes a big windfall tax on oil and gas companies and repurposing of VAT receipts from petrol/diesel (which spike when the price of fuel is high) to provide support for bills. I’ve heard arguments against the fine details, but without a major intervention there will be a huge flow of money from households, businesses and public sector organisations to electricity and gas companies. People will get into debt, be evicted, get ill or die from cold-related illnesses if household bills rise to the £5000 – £6000 a year as is predicted. Businesses could be even worse off, all non-domestic users are not protected by a price cap, and some customers are being quoted future estimates that are 1000% price rises – that makes millions of SMEs unviable all of a sudden. An intervention on the scale of the furlough scheme is required to keep the lights affordable.

Wholesale changes?

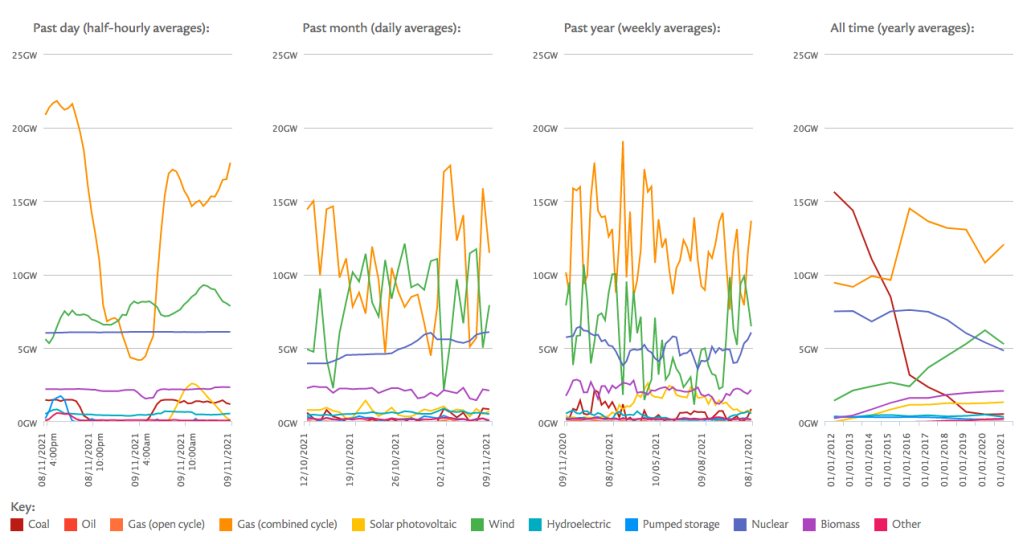

As I mentioned before we’re on a road to Net Zero, dispensing with fossil fuels so why does the price of gas still matter so much? Many years ago I switched to a 100% renewables electricity supplier because I’m committed to the cause but also I believed, naively that I’d be paying a small premium at the time in exchange for a product decoupled from the snakes and ladders nature of oil and gas markets. The wholesale electricity market means no one can escape from the jeopardy of fossil fuel instability – wholesale prices are set at the level of the most expensive form of electricity at the time. Even if you want to buy just wind, solar, biomass and hydro, it will be priced up at the same level as gas, if gas is expensive. Looking at real time data for electricity generation on a sunny, windy day sometimes renewables top out at 70% market share, it used to give me an enormous sense of well-being. That was before I knew about the wholesale market pricing mechanisms – even with a few % of natural gas in the mix we’re saving nothing.

The market is clearly weighted in favour of producers, rather than consumers and consumers will continue to be gouged by price spikes until we get rid of fossil fuels altogether, or in the medium term reform the market radically. Changing the rules of the game comes with headaches, contracts have been signed, if we move to a new pricing mechanism electricity companies will almost certainly lose out and there will be legal challenges. I can’t claim to have the answer when it comes to a pathway for market reform but this has been explored by energy and sustainability expert Michael Liebreich. If you see his latest blog you can see it proposes splitting the market into component parts, and is an excellent explainer of how the market works:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/uk-energy-crisis-time-split-power-market-michael-liebreich/

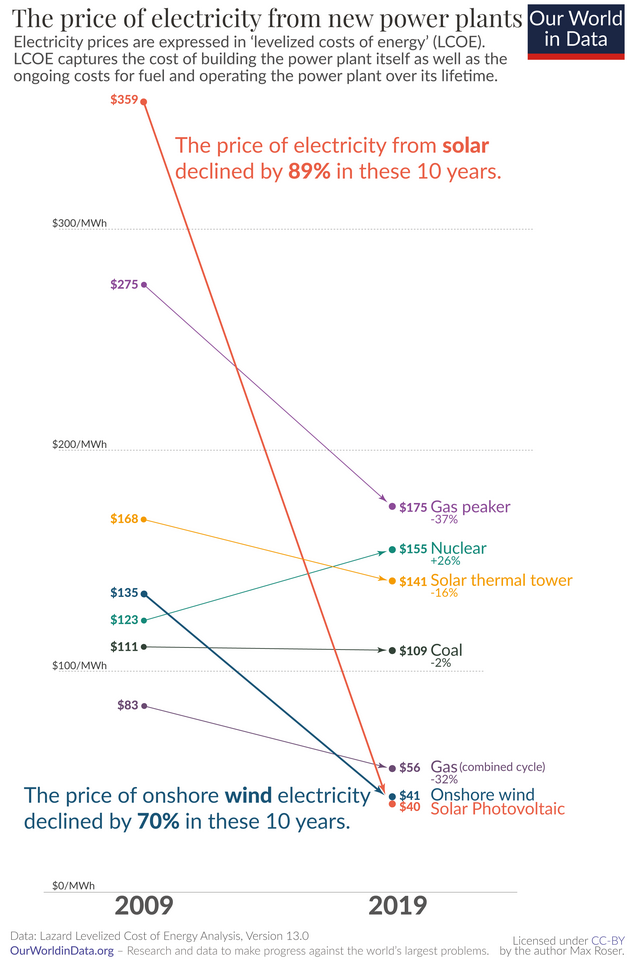

If I were to deviate from his proposals of a low carbon (renewables/nuclear) and fossil fuels split, to would be to keep renewables separate from nuclear, nuclear has never been price competitive – the major forms of renewables no longer need subsidy and in the case of solar and wind, are sure to get cheaper. I would like to see an aggregate price for renewables, the UK could use all eight different forms of renewable – hydro, solar, wind, wave, tidal, geothermal, biomass and biogas – all have their strengths and weaknesses and are at different stages of development. The cheapest – wind, solar and biomass – could subsidise the introduction of new forms of renewable that have been on the verge of deployment but not seen yet – geothermal, wave, and tidal.

White Knights

I can imagine, if I was a grown-up in 1973, feeling incredibly emasculated by the oil shock, which was followed by a two-year recession. The UK’s economy didn’t really recover until the late-80s, all of a sudden your quality of life, career and standard of living could be buffeted by things happening in countries thousands of miles away that were hard to understand the UK had nothing to do with. Could the gas panic be solved by an external intervention that could be as helpful as OPEC has been unhelpful to the West? I ask this question because both the US and Canada are major global producers of Natural Gas, and although many production contracts are signed off for years in advance, these countries could, if they really wanted to, turn on the taps for Europe, just like Russia can turn the taps off. On a scale of 1 to 10 how much does the US want to avoid a global recession, and avoid Europe feeling compromised by its opposition to Russia in Ukraine? At the moment no one is floating this as an option, just more piped gas from Norway and a few extra LNG tankers from Qatar and Algeria. Help from those lower volume producers isn’t going to cut it. North America has the power to help the rest of the industrial world – will it?

Those forever changes

One thing we learned in retrospect after the first oil shock is societies scouted around for alternative energy sources and energy saving measures – the shock might have precipitated permanent change but we were too lazy to bother. By the mid-80s aspirational energy changes fell by the wayside and we were back to bad habits because fossil fuels had become cheap and plentiful again – e.g. the average miles per gallon of new cars went down for about 10 years then regressed to pre-1973 levels. In the motor market, structural changes with the long-term phase out of combustion engines mean we’re set on a course of ditching oil no matter what. In the short term the Gov’t appears to be losing its nerve when it comes to electricity with Liz Truss saying she’ll ditch the green levy (this will hold up, but not eradicate investment in new renewables capacity) on bills – so that’s £150 off a £5000 bill – not a transformative difference to a household but a dent in our commitment to sustainability. The best we can hope for is Gov’t policy being a short term blip as the current administration will be voted out in 2024, and be replaced by one with one determined to make the 2022 gas panic the last fossil fuel shock we ever experience.