2023 – we’re living through what is quite frankly an unhinged era when it comes to our management of Planet Earth. Not a day goes by without an extreme weather event, a new data set showing ice loss or boiling oceans, and a pushback by right wing media stuck in the 1970s – like their readers. There’s a lot of pessimism about our ability to avert climate breakdown as we flirt with the 1.5ºc warming level. ‘I don’t want you to be hopeful, I want you to panic, our house is on fire’, says Greta Thunberg, the world’s most famous environmentalist (apart from David Attenborough). Thunberg’s statement is borne out of frustration that we’ve had 40 years of awareness of man made global warming, plenty of time to counteract it, but what we’ve done isn’t nearly enough.

It was so different in the 1980s when we had several big environmental wins, and they built on a process of identifying problems and dealing with them relatively swiftly. When I was growing up in the 1980s there were a number of industrial pollution issues that got resolved quickly, crucially they involved virtually no disruption to people’s lifestyles. Those quick and easy wins fed into a growing optimism about environmentalism, this led a breakthrough for the Green Party in the European elections of 1989, gaining 14.5% of the popular vote – 2.3 million votes. The Greens haven’t been close to that level ever since, though it’s not obvious how they repelled anyone who voted for them in 1989 but never again. So what was special about the 1980s and what happened before, in environmental terms?

The Industrial Revolution – environmental problems come to a head

History shows us that the process of industrialisation, building bigger and bigger cities, having high density housing, motorised transport and industrial methods of producing heat and power created unprecedented environmental problems. In the 19th century the concentration of people in London without adequate sanitation yielded the Great Stink of 1858. The sensory perception of London’s sewage problem in high summer just outside Parliament prompted policy makers to address an issue that had existed to some extent for centuries. It was a problem highlighted by eminent scientists immediately beforehand – Michael Faraday wrote a letter to The Times in 1855 describing experiments he’d carried out into water quality, he said, “Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface, even in water of this kind. … The smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water; it was the same as that which now comes up from the gully-holes in the streets; the whole river was for the time a real sewer.” Attempts to deal with the sewage started in 1857 with mixing chalk lime and carbolic acid into the River Thames – it wasn’t enough. Cue the intervention of Joseph Bazalgette. Bazalgette had actually been working as a surveyor for the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers since 1849 and produced a report in 1856. The problem was recurrent, the solution already existed, things came to a head in 1858 and the government finally took decisive action – building a network of 1100 miles of street sewers and 82 miles of mains sewers using Portland cement, a better mix of cement than what had been used hitherto. Work took place between 1859 and 1875, it cost £6.5 million – a major undertaking but by this point the Victorians understood the alternative – regular exposure to cholera and diarrhea.

A similar situation developed throughout the 1940s and 1950s with London’s air quality, which was hit hard by increasing amounts of coal burning by power stations and trains, and diesel emissions, especially from buses. This culminated in the Great Smog of 1952, of which the Met Office says, “The following pollutants were emitted each day during the smoggy period: 1,000 tonnes of smoke particles, 140 tonnes of hydrochloric acid, 14 tonnes of fluorine compounds and 370 tonnes of sulphur dioxide which may have been converted to 800 tonnes of sulphuric acid.[3] The relatively large size of the water droplets in the London fog allowed for the production of sulphates without the acidity of the liquid rising high enough to stop the reaction.” It’s estimated that this four-day fog event in December 1952 caused 10 – 12,000 deaths and 100,000 people became ill. By this point London had suffered from pea souper fogs for a century, but this was deemed to be so bad decisive action was taken, most notably the Clean Air Act of 1956 which legislated for smokeless fuels and the desulphurisation of flue gases emitted by power plants. Unsurprisingly the British Electricity Authority opposed the legislation at the time, exaggerating the costs of cleaning up power plant emissions and not accepting the nascent polluter pays principle.

Fast forward to the 1980s and due to past successes in tackling air and water quality there was the belief that tackling the worst excesses of industrial pollution were quite straightforward and could be achieved over a timeframe of 5 – 10 years at the most. Indeed there were four big wins at the time that confirmed it was possible to deal with the biggest environmental problems, not just local, not just national, but international problems if the world committed to tackling them. They were:

Acid rain

Acid rain – rainwater infused with sulphur and nitrogen dioxide – became a major problem in Western Europe and the Eastern Seaboard of the USA during the late 1970s and 1980s. Indeed thanks to a family holiday to Sweden in 1987 I saw the damage caused to Scandinavian forests with my own eyes. The corrosive effects of acids in the atmosphere had been observed as far back as the 17th century when John Evelyn, remarked upon the poor condition of the Arundel marbles, scientists started studying the problem in earnest in the 1960s, Swedish soil scientist Svante Odén’s 1968 paper is now regarded as a landmark study. The US responded with a number of acts – the Acid Deposition Act 1980 (this included widespread monitoring) and amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1990 that called for a 50% reduction in SO2 power plant emissions via a cap and trade scheme. In Europe and the rest of the world similar measures were pursued via the EU National Emission Ceilings Directive and the Gothenburg Protocol. A UK Government Acid Waters Monitoring Network report in 2010 reminds of the seriousness of the problem, “However it’s not all good news – whilst the waters are recovering, there is still a long way to go before the plant and animal communities are restored to full health. For example there are many rivers and lakes still devoid of brown trout or salmon as a result of the damage caused by acid rain.” This comment perhaps embodies the over optimism of the 1980s – Acid Rain was widely regarded to have been nailed by the mid-1990s and was rarely heard of again in the mainstream media.

Ozone layer

Addressing the hole in the Ozone layer perhaps involves the shortest timeframe in terms of problem identification to Global solution. Ozone levels had been observed in Antarctica since the 1970s but a report in 1985 about the Ozone layer being depleted by as much as 70% set alarm bells ringing around the world. This led to the Montreal Protocol, a global agreement to phase out the gases causing Ozone depletion – CFCs – which was implemented in 1989. Swift action was taken on the Ozone layer because it required one quick and easy change – a switch from CFCs to HFCs – that didn’t involve significant costs. What’s striking about the Ozone layer as an issue is that it will take a long time to heal, initial estimates were full recovery by 2050, now it’s more likely to be 2075 – but there’s no nihilism or fatalism around the issue. Also World Metrological Organisation studies show a significant seasonal variations in the Ozone layer. Note there are no Ozone Layer sceptics pointing out that the depletion is down to natural cycles, however, as there are no vested interests in the industrial chemical industries losing out from the CFC > HFC transition.

Lead in Petrol

Leaded petrol was the foremost air quality issue when I was growing up. Lead had been an ingredient in petrol as an anti-knocking agent since the 1920s. Growing suspicions about its effect on human health led to the foundation of the Campaign for Lead Free Air (CLEAR) in 1981, headed up by the former Director of Shelter, and future President of the Lib Dems, Des Wilson. The campaign resulted in the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution which published its findings in 1983, this confirmed that lead had serious adverse effects in children’s health and that ‘lead should not be added to petrol’. Within half an hour of the RCEP report being published, the Environment Secretary, Tom King, announced that the UK government would support the introduction of unleaded petrol, that oil companies would have to provide it on forecourts, and that car manufacturers would have to make engines that could use it. (It’s almost as if the Gov’t had a pre-prepared plan). Wikipedia notes, “CLEAR is regarded as a textbook example of how to run and win an environmental campaign.” That success was based on the charismatic leadership of Wilson, underpinned by the clear scientific evidence provided by hospital doctor Dr Robin Russell-Jones and scientific advisor Robert Stephens. Again petrol could be unleaded quickly and easily as the technological solutions existed that didn’t add significant costs to the petrochemical industry.

Saving the Whale

The International Whaling Commission was set up in 1946 and for many decades was a passive regulatory body of no note whatsoever. Whales, like all major sea life that can be exploited by man, were greatly depleted by industrial fishing in the post-war era. This was picked up in reports by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species in 1977 and 1981. These reports precipitated a sea change in the IWC (pun intended). Several non-whaling and anti-whaling countries joined the IWC during this time, these countries called on the IWC to update its practices, pushing for greater restriction and tight regulation of whaling. In 1982 the IWC voted by a 75% majority to pause commercial whaling, which was to start in 1986. While the agreement includes some minor loopholes, mass scale industrial whaling is over, and in 1994 the IWC voted to create 11,800,000-square-mile Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary. Certain pro-whaling countries, Japan, have been accused of lobbying and buying votes of developing nations, (the IWC has nine landlocked members), however overturning the ban on commercial whaling will prove difficult as it requires the same 75% majority vote. In an interview with Australian ABC television in July 2001, Japanese Fisheries Agency official Maseyuku Komatsu described minke whales as ‘cockroaches of the sea’. Maintaining and enforcing marine reserves will require a lot of vigilance going into the mid part of the 21st century as long as such attitudes exist.

2023 – what’s going on?

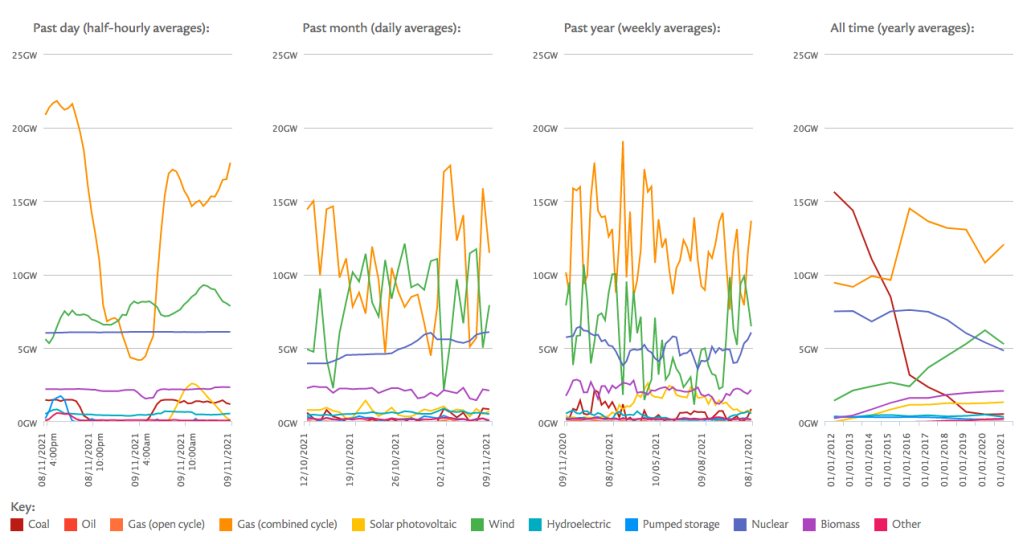

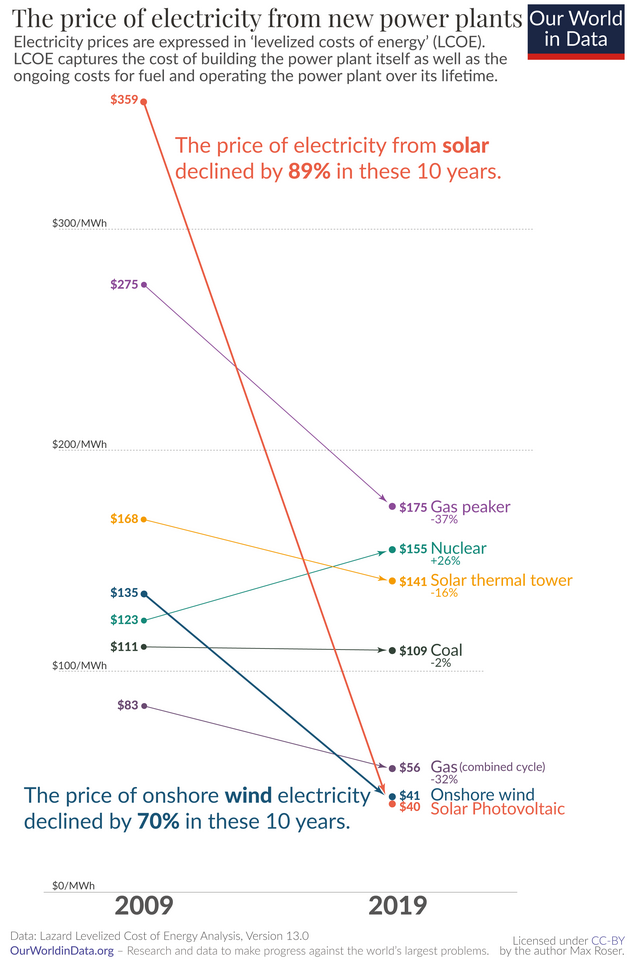

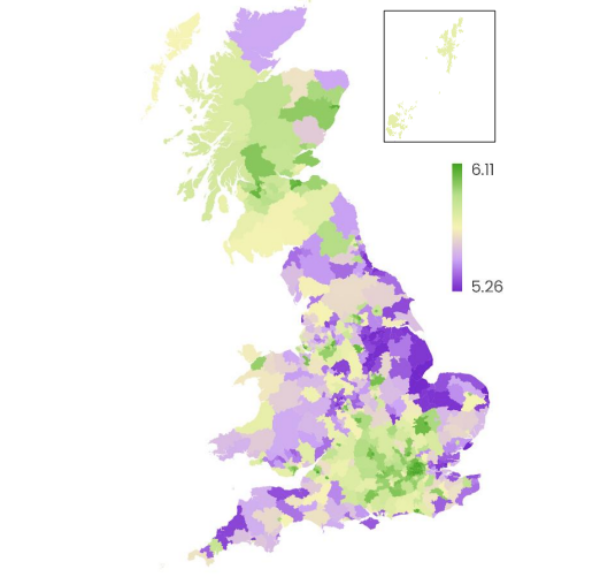

The phrase ‘clean tech’ barely existed in the 1980s, since then we’ve seen 1000s of innovations to help with industrial pollution, climate change and habitat restoration documented in New Scientist, The Engineer, Professional Engineering and Scientific American. Most of these never cross over into the mainstream broadcast media because TV shows such as Tomorrow’s World don’t exist any more (Deborah Meaden’s Big Green Money Show being an honourable exception). Because science information isn’t being fed into the mainstream we’ve lost the optimism that used to exist. When it comes to climate change there are decarbonisation processes for pretty much everything – electricity, heat, ground transport, raw materials production – but most people don’t know about them. It’s this information vacuum that’s creating the current headless chicken discourse surrounding climate change, and other environmental issues such as clean air. There’s a lot of finger-jabbing, not much communication and not much research by Joe Public. This is why people owning Electric Vehicles were conned into thinking they’d have to pay the ULEZ charge in outer London. I’m cautiously optimistic, clean tech consumer products like electric vehicles, solar panels and heat pumps are becoming increasingly mainstream across Europe, and as the price drops in many cases they don’t need any tangible political support any more. What we lack at the moment, however, is the optimism that we can solve the biggest environmental problems (even though we have the tools to do so), and the political leadership in the UK to tackle them. Thank God Joe Biden and Ursula von der Leyen have nothing in common with Rishi Sunak.