The 2024 election is in full swing and this week is Manifesto Week. All the major parties have shown their hand and it’s gratifying to see a positive response to the Lib Dems manifesto across the board. If the Lib Dems play their cards right they can hit a sweet spot – differentiated enough away from the major parties to offer a genuine and interesting alternative, but sensible and evidence-based enough not to have a load of looney tune policies that would weigh it down, like the Green Party has.

The Lib Dem platform often receives praise from people not necessarily close to us – in 2019 it received a particularly glowing review from Andrew Rawnsley in The Observer. However at the time our childcare, lifelong learning, and environmental policies were simply drowned out by the Brexit cacophony.

Hopefully this time round things will be different, although in what’s become a very shallow and superficial age it’s tough to get policies across compared to personality based content – hence Ed Davey’s long outward bound holiday. The following isn’t a complete list, I’m sure I’ve missed a few, but here’s a potted summary of the feedback we’ve received so far:

While Lib Dems have used It’s a Knockout style visuals to get onto TV bulletins there’s a lot of substance in our manifesto, drafted by Dick Newby (centre), now promoted by our party leadership

The Environment – Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace

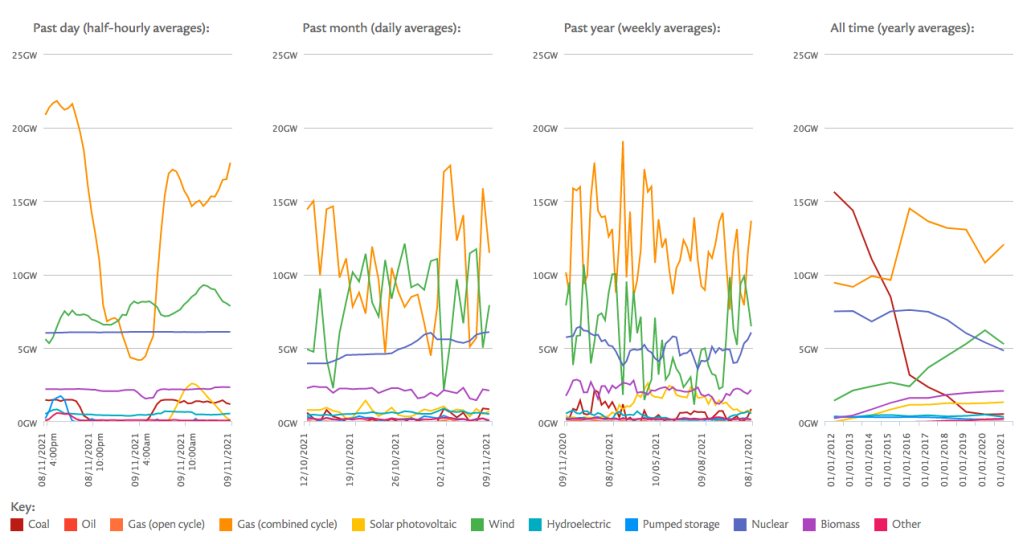

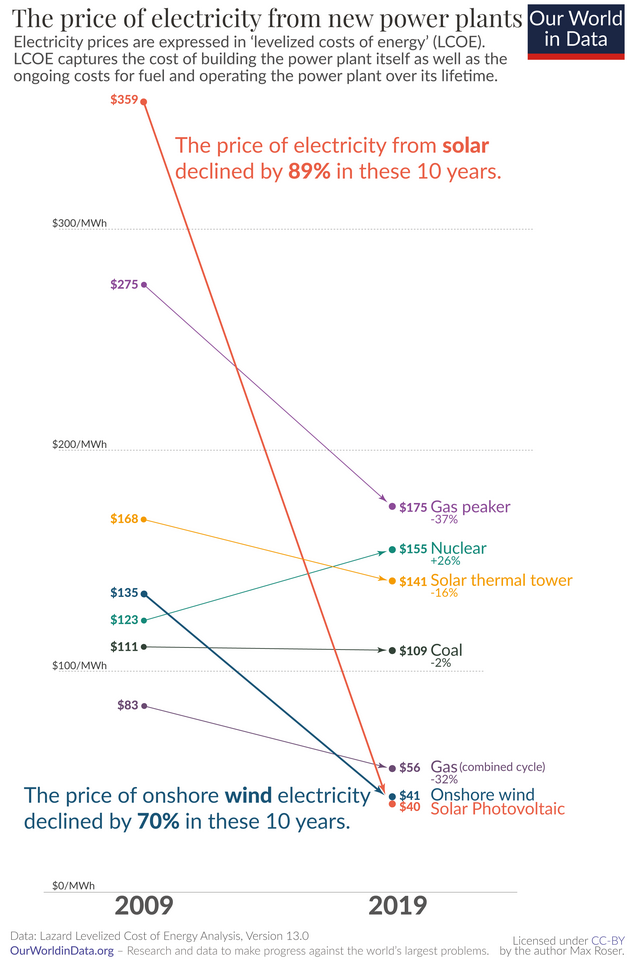

Both major environmental bodies have given their thumbs up to the Lib Dems platform, they are no pushovers and often tell the government it isn’t going far enough with their commitment to the environment. The Lib Dems have policies to address Net Zero, promoting the decarbonisation of the electricity grid, improved building performance, decarbonising transport but also improving habitat and reversing nature loss.

Earlier this week Friends of the Earth said, “The Lib Dems have released their manifesto and it’s encouraging It ‘appears to be an impressive document recognising the interconnection of the climate and nature crises with existing societal inequalities’ – Mike Childs, head of policy at FoE.” By contrast FoE said, “The Conservative manifesto falls so far short of what’s needed it reads like the party has given-up on the long-held conservative value of protecting the environment for future generations.”

Yesterday FoE said of Labour’s manifesto, “We really needed to see firm plans on how the biggest long-term challenges of our lifetime will be confronted. Yet the Labour Party manifesto skates over so much of what’s needed to tackle the climate and nature emergencies.” Clearly unhappy with Labour backtracking on its £28Bn Net Zero investment plan.

As you can see from the tweet below Greenpeace is equally positive about the Lib Dems manifesto, interestingly enough it gives less detail and hasn’t even bothered to critique the Conservative and Labour manifestos, presumably because they’re so weak they don’t merit comment.

Housing – Shelter and Crisis

In the Autumn the Lib Dems published its most detailed housing policy document in a generation, there was a lot to like about it – raising design and build standards, changing the relationship between landlords and tenants, aspiring to build 380,000 homes a year, of which 150,000 would be social homes. This contrasts with Labour’s commitment to taper up to 105,000 social homes a year over the course of a parliament. In response to the Lib Dems manifesto Shelter said, “The Lib Dems manifesto includes a cross-government plan to end homelessness, plus a social housing programme & scrapping the Vagrancy Act. Now we need the same level of ambition from other parties and commitments to End Homelessness. Let’s Make History.

With homelessness at record levels these manifesto proposals would put us on the path to tackling this growing crisis and offer hope to the thousands facing the injustice of being without a safe home.”

Shelter produced a lengthy thread on twitter picking out highlights from the manifesto, this included, “We applaud the focus on delivering Social Housing and we urge all parties to prioritise building social rent homes, not just Affordable Housing. The difference is crucial for those in need. The Lib Dems aim to end rough sleeping within the next Parliament and immediately scrap the archaic Vagrancy Act. We strongly welcome a target to end rough sleeping, and rights to emergency accommodation.”

Women’s equality – Fawcett Society

The Fawcett Society campaigns for gender equality and women’s rights. It produced a detailed commentary on the manifesto and how it relates to women. It said, “A new right to flex working, comprehensive reforms to childcare, increases to maternity and parental pay and reforms to parental leave will ensure that more families have a genuine choice about how they bring up their children and balance this care with their working lives. We are particularly pleased to see

Lib Dems put quality at the heart of their offer with a workforce strategy, and prioritising training including in supporting children with Special Educational Needs. They’ve also included proposals to public gender, ethnicity and disability pay gaps, alongside diversity targets. This is another major Fawcett campaign that we are delighted has been picked up. We know that when social services fail, women are most often the ones who step in to cover the gaps. It’s fantastic to see Lib Dems coming out with ambitious policy on adult social care.

The reforms proposed would mean that both men and women would be better supported to care for their loved ones, and that those working in social care will receive proper recognition of the difficult work they do, including fairer pay and a proper career structure.

We commend the party for putting this issue back into the campaign, and urge other parties to explain how they would resolve the crisis in adult social care.”

Health & Care – The King’s Fund

The King’s Fund is a leading Health & Care charity, its CEO Sarah Woolnough commented on the Lib Dem plans, “The Liberal Democrats are currently the only major English party proposing much-needed reform of social care, with plans to introduce free personal home care and a higher minimum wage for social care workers in England.

Free personal care doesn’t cover all aspects of a person’s care, and it’s unclear if the policy only applies to older people or also covers working-age adults living with disabilities. But the plan would still represent a significant step forward and increase many people’s access to state-funded care.

The party’s pledges to rescue NHS services touch on many of the key issues for patients, but could be summed up as good on ambition, light on detail. The aim to speed up access to GP appointments by recruiting 8,000 more GPs is a laudable ambition, but as the current government has found, recruiting more GPs and retaining existing ones is not easy, and without more detail on how the party would achieve this goal, it is hard to see how their promise of faster access to GP appointments can be met.

The party has pledged £9.4 billion additional health and care spending a year by 2028/29. Of that, £1.1 billion a year is to improve NHS buildings and equipment, and £3.7 billion a year is for day-to-day NHS spending.”

Unsurprisingly because this is such a wide area of policy The King’s Fund doesn’t give unequivocal support to every Lib Dems policy but we fare better than Labour who are criticised for not going into specifics for social care and the Conservatives for not offering enough money and for causing a workforce crisis via Brexit.

Education – The Sutton Trust

The Sutton Trust is an educational charity (a genuine one, unlike the IEA), that promotes social mobility via improved access to education. It provided a very detailed critique of the Lib Dems education agenda this week.

The trust said, “For the early years, the standout pledges are to give disadvantaged children aged three and four an extra five free hours a week (making it 20), to be extended to two-year-olds ‘when the public finances allow’, triple the Early Years Pupil Premium to £1,000 a year, and develop a career strategy for nursery staff, with the aim that the majority of those working with children aged two to four have a relevant qualification.

The commitments outlined for schools are wide-ranging, with many geared towards tackling the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers. Above inflation annual school and college funding increases would benefit all pupils, and start to redress the stagnation of school funding we’ve seen over the last decade. The ‘Tutoring Guarantee’ shows recognition of the huge impact this intervention can have in tackling the attainment gap when targeted to disadvantaged pupils.

It’s therefore welcome to see commitments in this manifesto for expansion of free school meals to all those in poverty (current FSM eligibility locks out 1.7 million children in families eligible for universal credit) and a qualified mental health professional in every school. More broadly, the pledge to remove the two-child cap on child benefits could have a major impact on tackling disadvantage and poverty.

The headline policy to reinstate maintenance grants for disadvantaged students ‘immediately’, to make sure that living costs are not a barrier to studying at university, is absolutely right. However that should also be accompanied with a rise in the overall amount, to make sure students have more money in their pockets.

Our research has shown that students are increasingly skipping meals and taking on extra paid work at the expense of their studies to make ends meet. The poorest students also graduate with the highest levels of debt – a barrier for some wishing to go on to higher education. This must be a priority for the next government.”

By contrast The Sutton Trust points to glaring gaps in Labour and Conservative education policies – director of research and policy Carl Cullinane said, “To achieve their mission, Labour will have to go way beyond the policies set out in their manifesto. The Conservatives’ manifesto is relatively light when it comes to the education sector, given the scale of the challenges facing the sector. There are clear issues with some of the well-trailed policies it contains.”