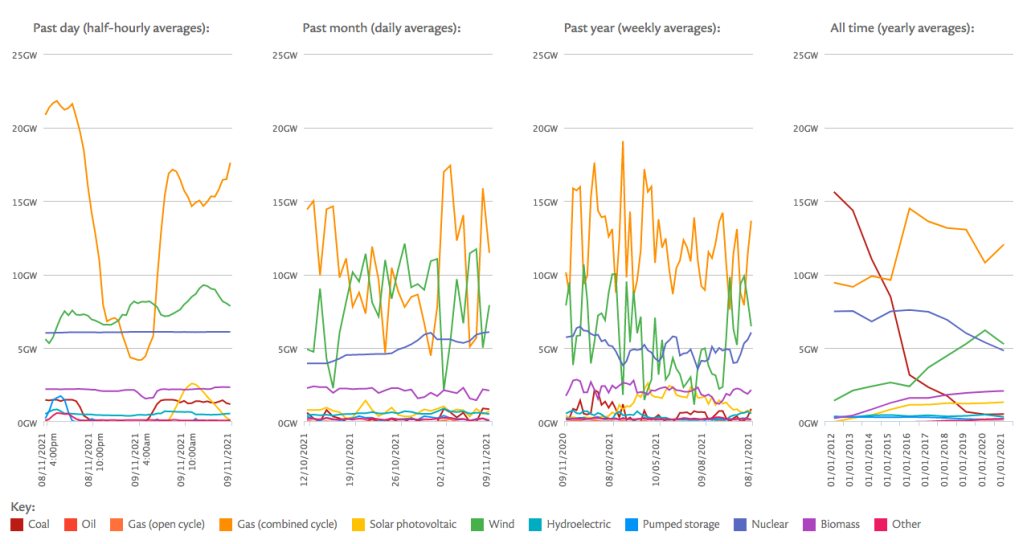

You won’t have noticed it, but this week has been momentous for the electricity grid. Six out of nine UK nuclear power plants are offline at the moment, so nuclear power generation has dropped to a decades-long low of just 2.5GW. This compares to a norm of 4.7GW when all our plants are running normally. Nuclear generating just 2.5GW asks questions about just how valid the concept of a ‘baseload’ is, and if you need one at all, how substantial does it have to be? The fact is that if we can operate in the middle of winter, when demand is highest, on just 2.5GW, it would only take a few years to replace nuclear, either with battery storage or other forms of generation that mimic its constancy.

Pathways to phase out

In the last 15 years the growth of renewables has been pretty remarkable, up from 5% market share in 2008, to 45% market share in 2023. It’s likely that by 2030 the UK will be a renewables dominant country, up to 60 – 65% market share. To achieve this it only has to continue what it’s been doing for the last 15 years, add the same kinds of renewables – wind and solar – and add in some grid balancing measures such as battery storage and demand management.

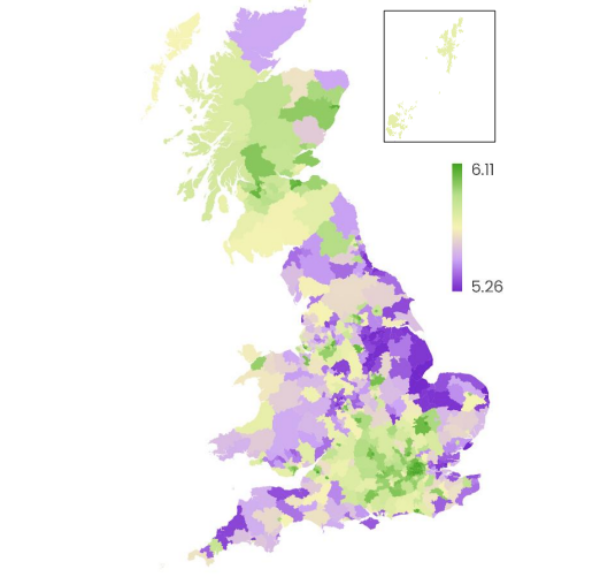

Certainly with wind, which now has a 25% market share of UK electricity, there’s a sense we’ve only just got started. Five years ago the average capacity turbine was 3.5 megawatts, now the Dogger Bank wind farm is deploying 13 megawatt turbines. The Dept for Energy Security and Net Zero, those famous tree-hugging hippies, believes we’ll be using 20 megawatt turbines by 2040. It’s also the case that we’ve not even tapped into the areas where the best wind resource is – North of Northern Ireland and West of Scotland.

In the past the long farm-to-shore cabling, deep water and long connections to population centres has held that back. Improvements in cabling tech and the development of floating wind farm designs means putting the biggest turbines where there is the most wind has become more likely. If not, we could still have multi-gigawatt farms out in the North Sea, Irish Sea and the South West approaches.

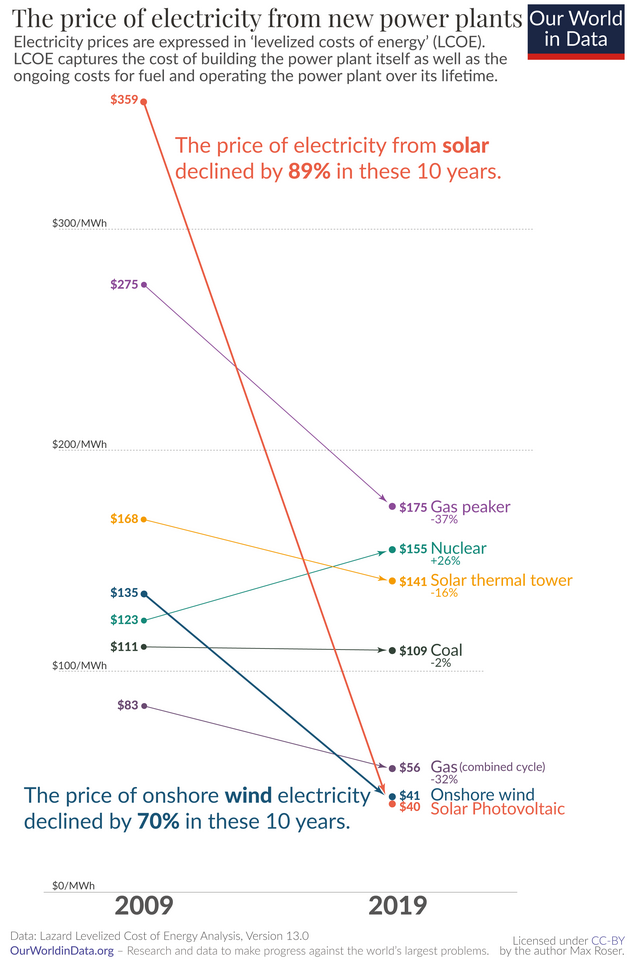

As a long term follower of clean tech, there is a long march to renewables dominance that is quite frankly irresistible – solar has seen a huge price drop in the last 20 years, the same goes for wind, for battery storage and for tidal stream. That’s backed up by studies that demonstrate the huge potential of certain renewables we haven’t started using yet, such as geothermal.

Last year the British Geological Survey mapped the geothermal potential of Carboniferous Limestone in detail for the first time, it estimates there is the potential to recover between 106 to 222 gigawatts of thermal heat from the rocks under the Midlands and the South. So that’s just one part of the country, and prior to that survey it was generally assumed that granite rock under Cornwall and Aberdeen had the best potential for geothermal power.

It’s a climate emergency, we don’t have the time

When it comes to nuclear fission, on the other hand, news of improvements are thin on the ground. Nuclear has always needed subsidy and the latest types of nuclear power plant are dogged by significant cost overruns and time delays. Hinkley Point C is expected to cost £32Bn, and Sizewell C, if it is ever built, is estimated at £30Bn.

Because plants are difficult and complex to build it takes time, and because some Brain of Britain decided it was a good idea to build particularly big nuclear power plants, they turned Hinkley and Sizewell into megaprojects – which are harder to manage and control. It will take 15 – 20 years to build these plants – for climate change purposes we simply don’t have 15 – 20 years. Renewables can be deployed as modular units which means it’s much quicker to install them and much easier to keep control of costs.

Why have governments around the world persisted with nuclear when it has been undercut by non-hydro renewables for some time now, and those forms of generation have gone from fringe to mainstream? Certain voices in the energy debate have given a lot of credit to the constancy of nuclear – essentially you turn a plant on and it produces the same amount of electricity for decades. This contrasts with the intermittency of wind, and solar only operating during daylight. The historical weaknesses of wind and solar are to an extent reduced by using bigger turbines and putting them in the best locations, and solar panel/battery combos, but it is true that output of wind and solar varies wildly.

Can other renewables counteract this? Biomass and biogas are on demand and can be fed into the same plants formerly used to burn coal (e.g. Drax), tidal and wave are predictable and constant, and geothermal can either be on demand via a twin borehole system, or constant with a closed loop.

Coping with Net Zero demands

Replacing a relatively small amount of nuclear isn’t a problem if you weren’t attempting to reach the wider net zero goal, which involves decarbonising all road transport and heating. This will involve using electricity where oil and gas have been dominant for decades. A recent study by Hannah Ritchie shows that to electrify all road transport – cars, buses, trucks etc – you need to increase the grid by 40%. How would you do this?

The UK has the potential to tap into gigawatts more of wind, has a wave and tidal potential between 30 and 50 gigawatts, has the huge geothermal potential mentioned above and battery storage too. At the moment lithium-ion batteries are dominant, it’s expected in the next 15 – 20 years it’s possible we’ll see more cheap, low density sodium-ion batteries come onstream, these won’t need lithium, nickel or copper, and sodium is an abundant resource so the sky’s the limit in terms of battery storage capacity – could be hundreds of gigawatts if we’re committed to a big back up supply.

Other studies have shown that the electricity demand for heat pumps to replace natural gas central heating is more significant than for electric cars. While this is true, and the demand for electric vehicles and heat pumps would put a massive strain on the grid, the UK has 28 million homes and we’re installing heat pumps at a rate of only 60,000 a year.

Even if we hit the government target of 600,000 installations a year by the late 2020s, it would still take 47 years to replace every gas boiler. Either we’re going to come up with a radical plan for the 2030s and 2040s to decarbonise heat or it’s going to be a grindingly slow process going well into the mid century and beyond. That’s why Bloomberg believes heat pumps will only add 5% to the UK’s electricity demand by 2030.

Even so, we can’t be complacent about future demands being placed on the grid, we’ve decarbonised electricity hugely since 2008 by phasing out coal, that’s come in the context of falling usage since 2009 driven by improved efficiency of appliances. Can we increase the market share of renewables and increase overall production by 20 – 30 gigawatts a day?

The UK is lucky in that it can call on eight different forms of renewable power – wind, solar, hydro, wave, tidal, geothermal, biogas, and biomass – we’re uniquely well placed to go 100% renewable with a particularly strong wind and tidal resource. To do so, however, we need to prove that we’re a proper country given to long term commitments, which is what Net Zero requires. The recent decision to cancel HS2 suggests we’re not a serious country at the moment when it comes to infrastructure or Net Zero. Hopefully that will change with the election in a few months time.

Useful further reading:

Hannah Ritchie’s study into EV electricity demand:

https://www.sustainabilitybynumbers.com/p/uk-ev-electricity-demand

UCL study into the electricity demand from heatpumps:

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/energy/news/2022/feb/heat-pumps-uk-homes-how-will-they-be-powered